1991: Michael's a Killer

MJ's Bulls take control by annihilating (and humiliating) everyone in their way

Some figures are so important, the history that follows simply can’t be understood without them. More than one of them is named Michael. The American Film Institute lists The Godfather as the second-greatest American film of all time, and while their rankings may occasionally confuse “greatest” with “longest and oldest” (hello, Gone With the Wind), the stuffy bastards have a point here. Michael Corleone’s transformation from civilian war hero to crime boss antihero in The Godfather can easily be seen as the template for the character studies that are the lifeblood of our current age of “Prestige TV.” Likewise, for fans of a certain age the discussion of NBA superstardom begins with Michael Jordan’s Bulls: a team that would go on to define a decade of basketball and pop culture. If Michael Jordan’s killer instinct looks a lot like Michael Corleone’s, Kobe Bryant could easily be mistaken for Tony Soprano: an Italian-American antihero for a new millennium, biting his idol’s moves and cultivating an unhealthy rivalry with the other outsized personality inside his family (Shaq in this analogy ably playing the role of passive-aggressive Soprano matriarch Livia, with Zen-master coach Phil Jackson stepping in to mediate as therapist Dr. Melfi). But things weren’t always that way. There’s no template to follow without the original. This is the story of how Michael became Michael.

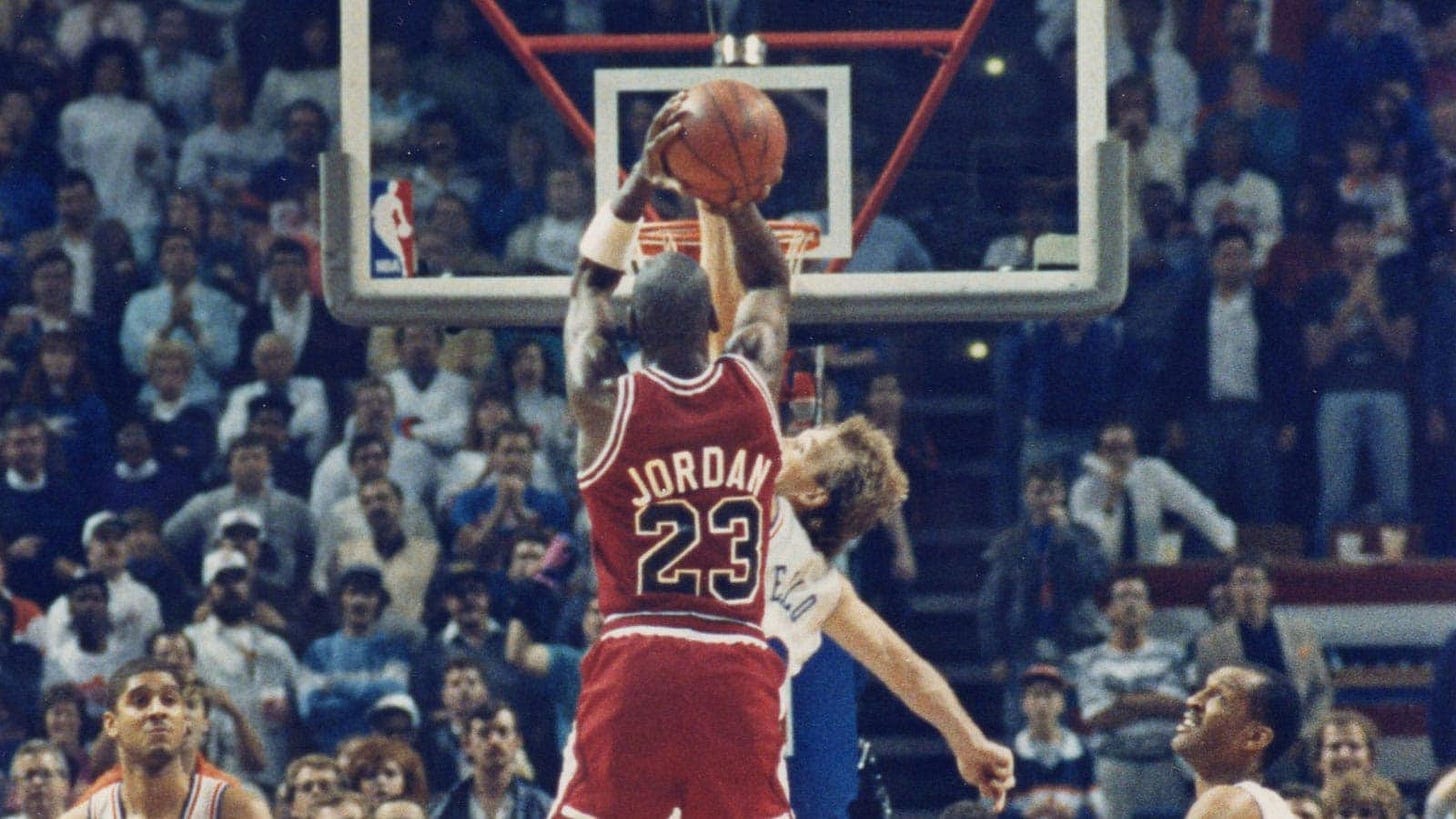

Our story begins in 1990, with Michael Jordan the most popular figure in basketball, and perhaps in all of sports. Six years into his career, he was a 6-time All-Star, 5-time scoring champ, and league MVP winner. But not yet a champion. He had moments of playoff brilliance, like the 1986 playoff game against conference heavyweight Boston in which Michael scored 63 points, spurring Larry Bird to call him “God disguised as Michael Jordan.” He’d also proven he wasn’t afraid to get a little blood on his hands, famously eliminating the favored Cleveland Cavaliers with “The Shot” in 1989. But carrying out hits is a long way from ordering them. In both cases, Michael’s Bulls had been sent packing before the NBA Finals rolled around—a nice trip to Sicily, perhaps—while the league’s Capos handled the real business of deciding NBA championships. After several years of stability and good vibes presided over by the effortless charisma of Magic Johnson’s Showtime Lakers, the “Bad Boy” Pistons were the ones calling the shots at the turn of the decade. Cold, calculating, and ruthless, the Pistons pushed the boundaries of the basketball rulebook and dared the refs to blow the whistle. Isiah Thomas was the type of captain who wouldn’t think twice about ordering a hit at a hospital or turning James Caan into Swiss cheese at a toll booth. With their brutal play terrorizing the league, the NBA belonged to the Pistons until someone else could snatch it from them.

There was no shortage of would-be usurpers. The Godfather largely takes place in crowded rooms—between the deep bench of the Corleone entourage and the other four Families vying for control, there are too many brooding Italian men in dark suits to keep track of. Michael had a legitimate claim to power following his father’s retirement and his brother’s murder, but in the brutal world of organized crime, power didn’t change hands without bloodshed. Michael Jordan’s claim to the NBA throne was no less legitimate—his individual bona fides confirmed by a near-unanimous second MVP win for the 1991 season, and his Bulls looking like the best team in the East heading into the playoffs—but if he wanted the throne, he’d need to prove it in the cutthroat elimination of the postseason. While the Lakers and Portland Trail Blazers would battle it out for supremacy in the West (more on Portland next year), the Bulls would draw from Michael Corleone’s playbook to clear their own path in the East.

In the final act of The Godfather, Michael Corleone’s power play coincides with his son’s baptism. Holy vows are intercut with ungodly violence, as we’re shown various Corleone henchmen assassinating rivals across town, cementing his rule over the Five Families in New York City and beyond. With these actions, Michael himself is effectively being baptized into the title of Don, ending the war by burying his enemies. The early rounds of the 1991 playoffs were Michael Jordan’s baptism, where he didn’t just beat his eastern rivals, he broke them. In round one, the Bulls swept Patrick Ewing’s Knicks with a whupping so thorough it cost New York coach John MacLeod his job—they’d eventually replace him with a wartime consigliere. In the conference semifinal round, a 4-1 Bulls win reduced the Philadelphia 76ers to a smoldering ruin, basically costing them their young superstar Charles Barkley who would make the smart move to betray Philly for Phoenix only a year later. Michael’s control over these peers extended well beyond these playoffs—and even beyond the court. As evidence, look no further than 1996’s Space Jam—Michael Jordan’s big screen debut—wherein he tricked five fellow NBA players (including Ewing and Barkley) to appear alongside him, only to have their basketball abilities immediately stripped away, their live-action selves humiliated (Charles Barkley has his shot blocked by a 14-year-old, a therapist asks soft-spoken Patrick Ewing about his sex life), and their would-be-slaver alien avatars embarrassed by Bugs Bunny blowing them up with dynamite and taking off their shorts to laugh at their big stupid butts. Even in Looney Tune land, these guys couldn’t get a win.

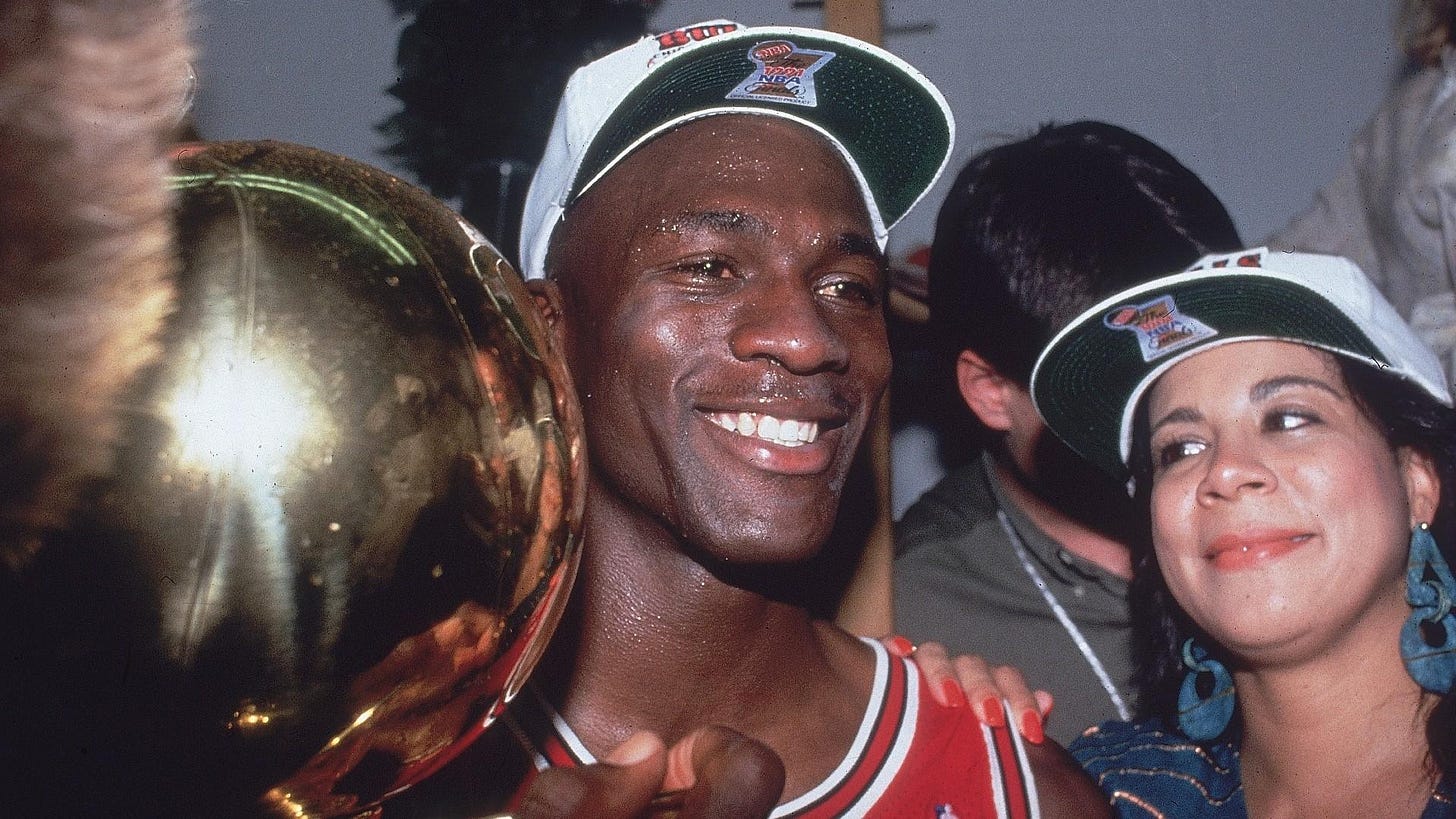

While breathtaking in its near-perfect choreography through two rounds (the Bulls went a combined 7-1 against their first two playoff foes), Michael’s baptism by fire wouldn’t be complete without another face-to-face with the Pistons. While the previous basketball was all business, this matchup was personal. And after two years under Detroit’s thumb, the Bulls smelled blood in the water. The confrontation was brief and one-sided: a 4-0 sweep, ushering the Bulls to their first Finals berth and the Pistons to an unceremonious exit. To leave it at that would be underselling this moment though. This was revenge for years of abuse. This was tying up the last loose end so tight it couldn’t breathe. Michael’s destruction of the Bad Boys didn’t spur a dramatic coaching change like in New York or superstar exit like Barkley from Philadelphia. The two-time champion Pistons remained fully intact, but the life was gone from their eyes. Over their remaining seasons together, they’d muster a single playoff appearance (a spiritless first round lost). 1990 Finals MVP Isiah Thomas wouldn’t even be extended the honor of a spot on the 1992 Olympic Dream Team the following summer. The series had been a cold-blooded garroting, emphatically striking the last name from Michael’s hit list. The final scene of the 1991 NBA Finals is Michael’s coronation: Magic Johnson and the Lakers bowed in reverence, kissing his ring; the specter of Detroit hanging thick over the proceedings, a gruesome example of what these Bulls are capable of; the rest of the NBA watching helplessly from the hallway as their title windows swing shut.