2004: The Academy Doesn’t Take the Bait

Guys, I'm sorry, no, there's a mistake. Detroit, you guys won the NBA championship.

The term “Oscar bait” carries insidious connotations. First, it implies that the Academy Awards do not in fact always reward the most deserving performances and have biases that can be played on. Second, it implies there are movies made with the intention of—perhaps solely for the purpose of—exploiting this fact, and that these manipulators are being rewarded with cinema’s highest honor. We all know Oscar bait when we see it. A movie about the magic of movies? Good start. Protagonist with a mental or physical disability? Oscar’s listening. Historical epic, war movie, and/or great man biopic? Oscar is frothing at the mouth. A 2014 UCLA study backs up our hunches with hard statistical fact, finding correlations between Academy nominations and certain genres, keywords, and plot elements, some positive—such as “show business”, “war crime”, and “family tragedy”—and some negative—“zombie”, “breast implant”, and “black independent film.” Yikes. Even if the Academy can be baited, surely no respectable actor would stoop to such cheap tactics, right?

The allure of winning an Academy Award regularly draws even Hollywood’s best and biggest stars to Oscar bait. Consummate actor’s actor Gary Oldman disappeared into interesting genre roles for decades and was ignored by the Academy until he met them on their terms, slapping on prosthetic jowls and jamming a cigar into his mouth for Darkest Hour and instantly hitting pay dirt (if you’re keeping score at home that’s dramatic physical transformation + “great man” biopic with a WWII multiplier). A desperate Leonardo DiCaprio—arguably the most respected actor of his generation—climbed into a bear carcass and ate raw bison liver in 2015’s The Revenant to finally, through sheer effort, get his own Oscar (though teaming with reigning Best Director, Best Screenwriter, and Best Picture winner Alejandro González Iñárritu likely greased the Academy’s wheels a bit too, as did the magic words “based on true events”). All you need is one statue to earn the prefix “Oscar-winner” and join the exclusive club. Maybe it doesn’t matter how you get it.

There’s a strong parallel between Hollywood chasing Oscars and NBA veterans chasing championships. The term “ring chasing” is applied (again, often derogatorily) to a player late in their career jumping to a contender. Think about Clyde Drexler or Charles Barkley joining the Houston Rockets at the tail end of their primes after flaming out in Portland and Phoenix respectively, Ray Allen ditching Boston to join the Miami Heat superteam in 2012, or basically anyone who signed with the Golden State Warriors in the last half of the 2010s. Winning a ring this way is opportunistic, sure, but when legacies are evaluated by championships, why wouldn’t players jump at every chance they get?

In the summer of 2003, two-time MVP Karl Malone and nine-time All-Star Gary Payton were thinking along these lines. Malone was 40 and on the cusp of retiring without a ring. He’d spent his entire 18-year career with the Utah Jazz, leading them to two NBA Finals and five Western Conference Finals, but that team hadn’t been a contender since the nineties. Payton was 35 and had just been unceremoniously dumped by the Seattle SuperSonics to the dead-end Milwaukee Bucks after 13 years, including a three-year span from 1994 to 1996 during which Seattle was the winningest team in the NBA yet remained ringless. Neither could resist the allure of Los Angeles—the Staples Center rafters bowing under the weight of so many banners and coach Phil Jackson’s knuckles dragging with the heft of 10 championship rings—and oddsmakers couldn’t resist the allure of so many Hall of Famers teaming up. The season looked over before it started.

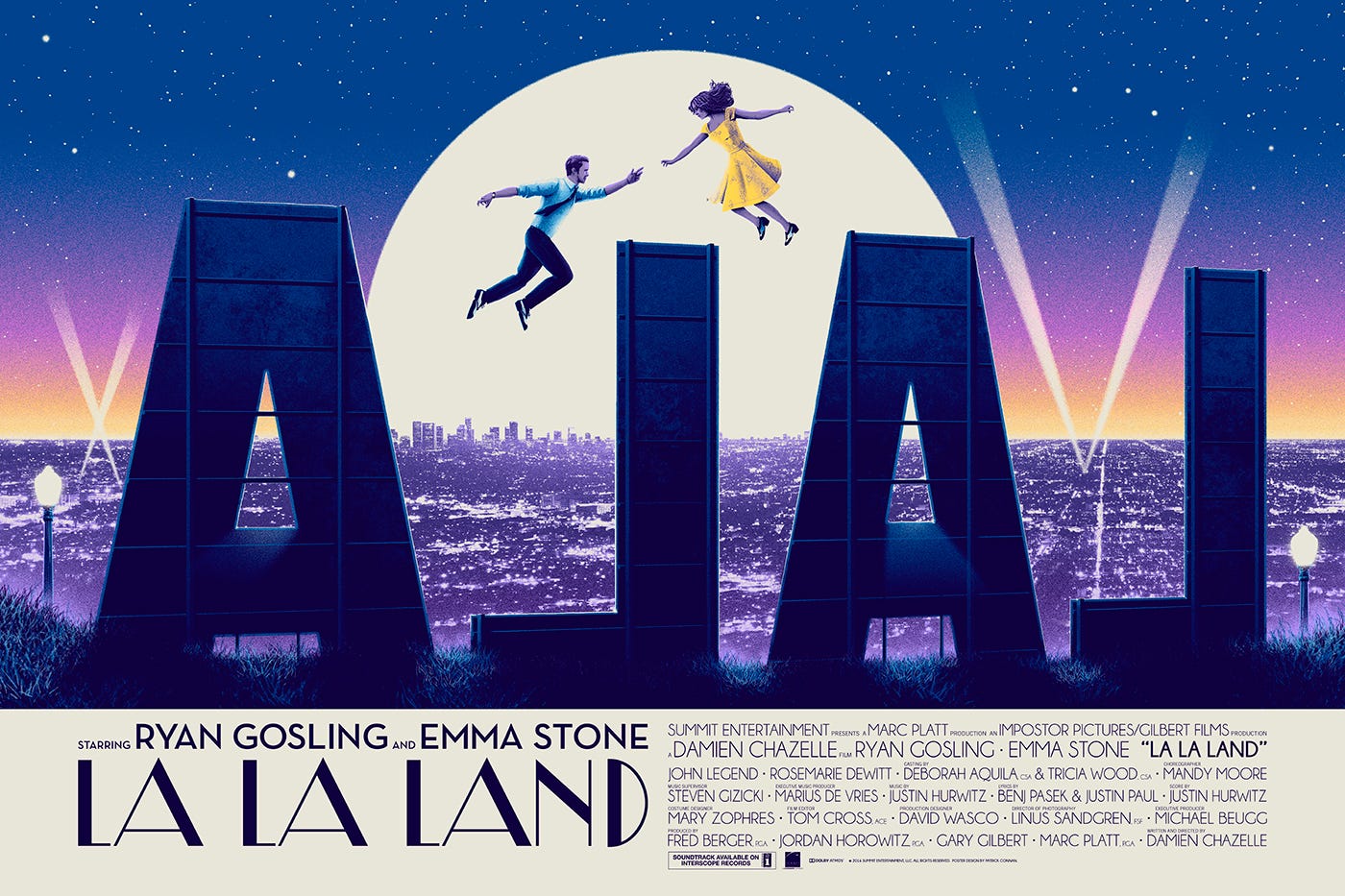

But NBA titles aren’t won on paper any more than Oscars are. In the run up to the 2017 Academy Awards, one movie dominated the conversation. La La Land’s Oscar prospects were self-evident from its title alone: a movie musical about showbiz set in the Academy’s backyard. Considering it was also written and directed by previous Oscar nominee Damien Chazelle and distributed by the same studio that somehow got Crash a Best Picture win in 2005, they had to like their odds. The only real competition for the top prize was a queer coming-of-age story from a relatively unknown Black filmmaker named Barry Jenkins and distributed by an independent studio (A24) with no history at the Oscars. Our UCLA research team already told us how this will end.

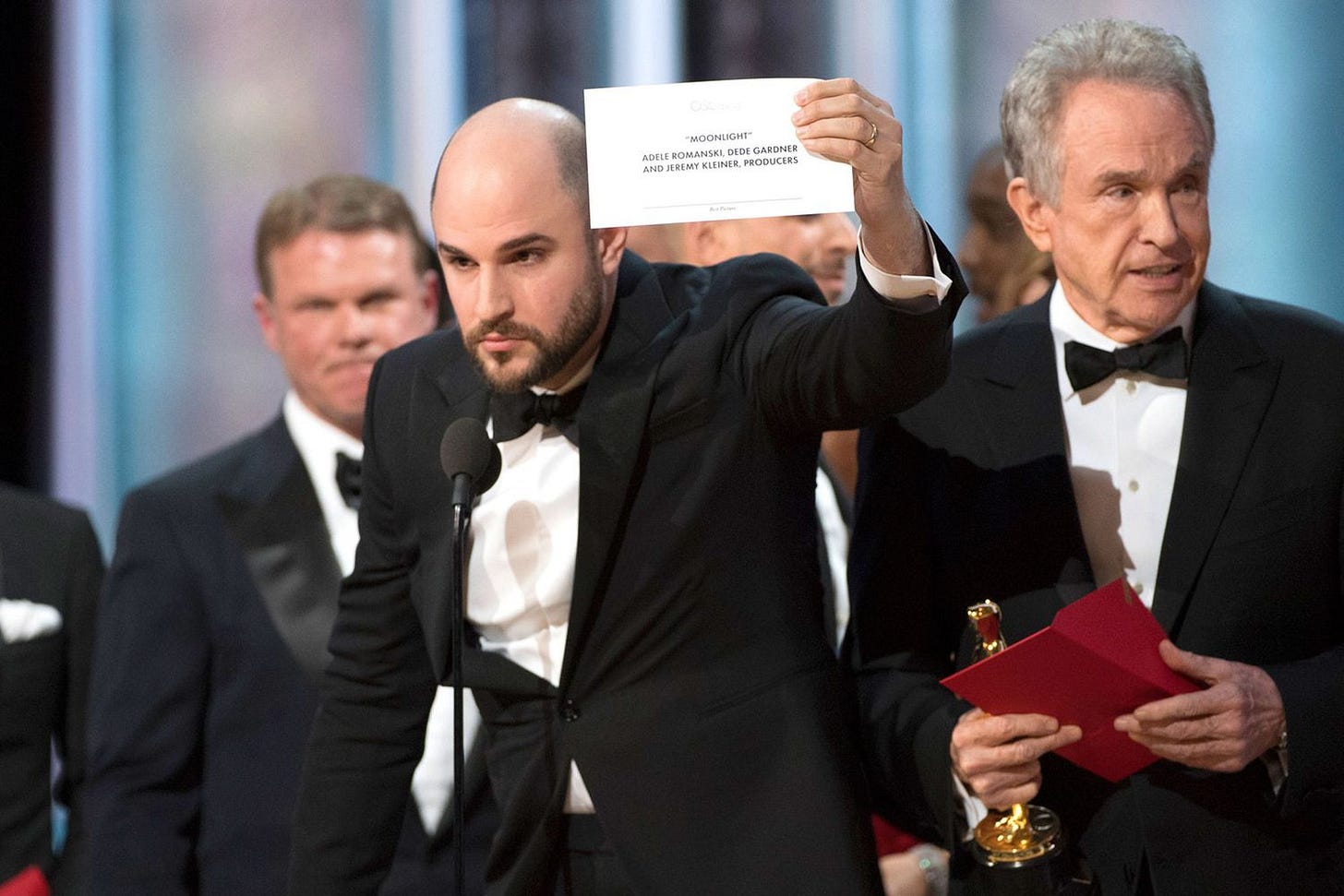

When La La Land was nominated for a record-tying 14 Academy Awards—joining Best Picture winners All About Eve and Titanic—the black tie ceremony felt like a mere formality. If the ABC broadcast had borrowed ESPN’s win probability graphic for the night, La La Land’s chances would’ve started somewhere around 80% and only crept higher as it racked up below-the-line wins for production design, cinematography, score, and songwriting. By the time Warren Beaty and Faye Dunaway took the stage to announce Best Picture, it had serious momentum on the heels of two major wins: Chazelle for Best Director and Emma Stone for Best Actress. The win probability graphic capped out at 99.9% as La La Land’s producers were giving their acceptance speeches on stage, a curious commotion stirring behind them. You know the rest, and if you don’t, just watch the clip. In the most dramatic way possible, the Academy taught us the only thing it loves more than a Hollywood story is an underdog.

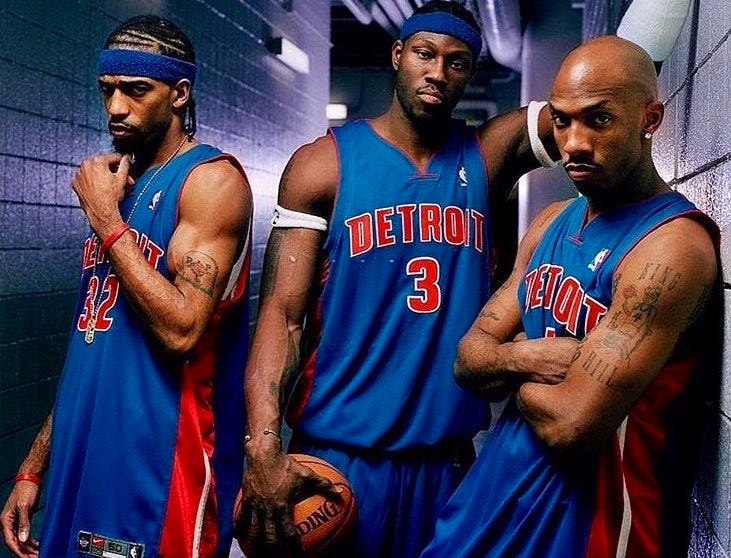

The 2004 Finals stage was set for an underdog story to unfold there too, featuring two dichotomous competitors primed to re-litigate the NBA’s obsession with aggressively alpha-male superstars. On the one hand, the Los Angeles Lakers were a swaggering juggernaut of talent undermined only by the two warring factions within the locker room—Shaquille O’Neal and Kobe Bryant, both believing the team should belong to them. On the other, the Detroit Pistons’ roster was a sort of life raft for castoffs—flawed players who found their identity as part of a collective, covering for one another’s weaknesses. Ben Wallace was their only All-Star, and he couldn’t play a lick of offense. Chauncey Billups was a lottery pick bust, already on his fifth team in five years, Rip Hamilton was a shooting guard seemingly allergic to the three-point line, beanpole forward Tayshaun Prince’s slender frame couldn’t handle NBA physicality, and Rasheed Wallace’s short temper couldn’t keep him on the court. L.A. may have had too many alphas, but surely an NBA champion needed at least one?

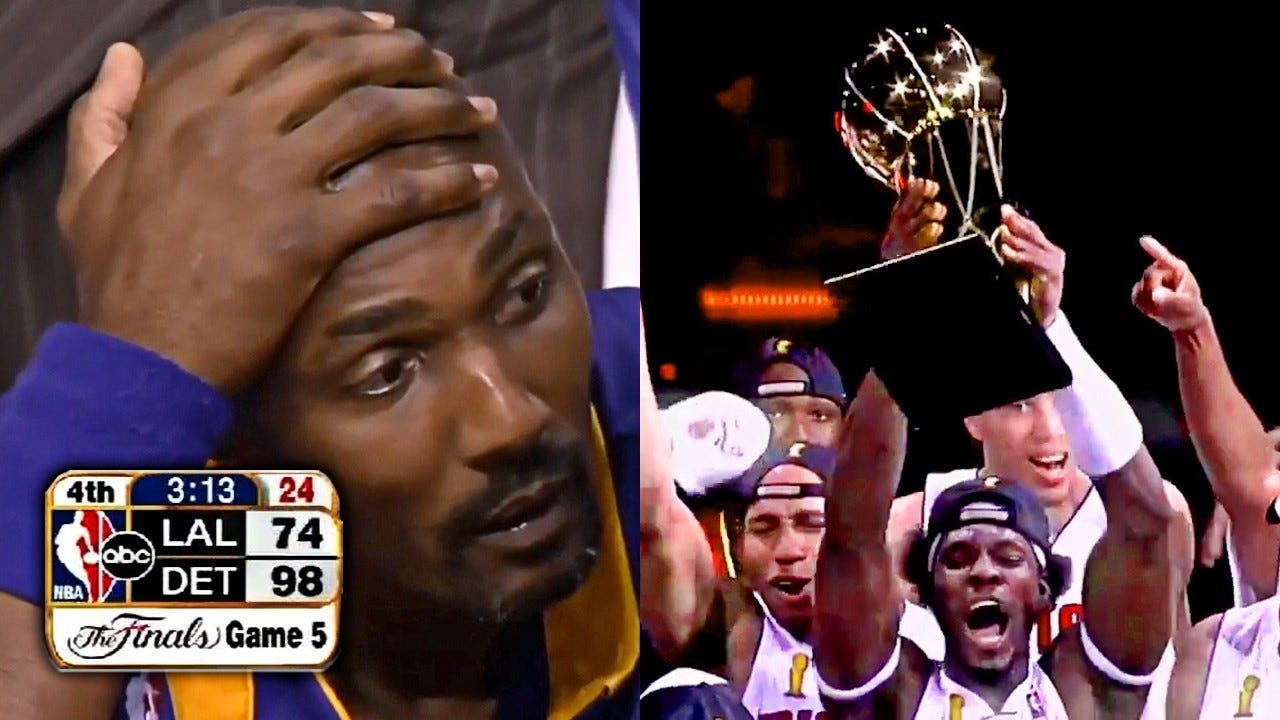

When L.A. survived the Western gauntlet of the reigning champ San Antonio Spurs and MVP Kevin Garnett’s surprise top seed Minnesota Timberwolves, many felt the rest was a foregone conclusion. Pundits were nearly unanimous in their predictions. L.A. media pleaded for a quick end to a dull series—one Los Angeles Daily News headline read “Sweep would keep fans from falling asleep”—and The Detroit News was already rehearsing its gracious loser face: “Who cares that they now face the best team on the planet in the NBA Finals, who could embarrass them in four games?”. Vegas gave the Lakers an 85% chance to claim the title; no Finals favorite with odds that high had ever lost. Everyone was half right: the series was indeed quick, but it was Detroit blowing out L.A. in five games. There wasn’t a mistake. This wasn’t a joke. The Detroit Pistons had won the NBA Championship.

It’s tempting to write both events off as flukes. After all, no Finals underdog to date has overcome longer odds than Detroit did in that 2004 series, and certainly no Best Picture drama has even approached the La La Land debacle. I prefer to think of both as inflection points.

The Academy continued to surprise over the coming years, naming its first non-English language Best Picture winner in 2020, and arguably squashing the definition of Oscar bait when it handed Everything Everywhere All At Once—a movie whose top IMDb keywords include “multiverse”, “kung fu”, and “dildo”—a record six above-the-line Oscars in 2023.

The Pistons’ win shattered the NBA hierarchy, scattering the Lakers’ stars to the four winds—Shaq was shipped to Miami, Malone retired ringless, Payton continued his ring hunt in Boston, and Kobe was left holding the reins to a shell of a team, not even talented enough to make the playoffs—and restoring some semblance of competitive balance between the conferences.

It’d take fourteen years for Vegas to regain the confidence to give any Finals matchup odds that lopsided again, and it will take at least that long for the memory of the La La Land mixup to stop hanging over every Best Picture announcement—talk about legacy, just listen to Al Pacino’s bizarre delivery of, “my eyes see Oppenheimer,” as if the truth in the envelope is now subjective.

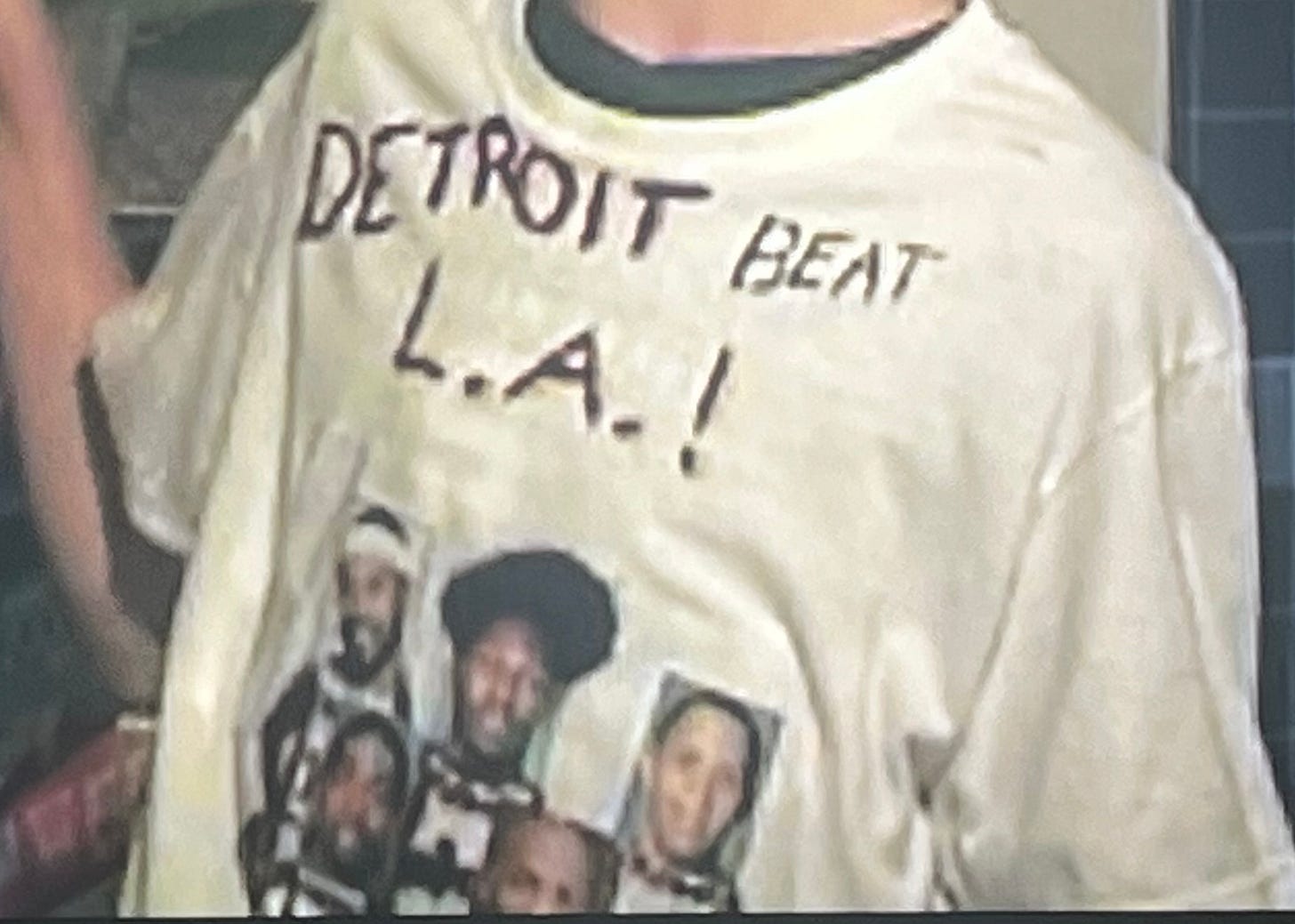

But the legacy of the 2004 NBA Finals is bigger than that, at least for me. With every game, my family TV room buzzed with the same palpable energy present in the Dolby Theater that Oscar night—the euphoria and disbelief of witnessing something unprecedented in real time. In Barry Jenkins’s brief acceptance speech, he mused that this was beyond his wildest dreams. I could relate. But unlike a dream—or the speculative world of odds, win probabilities, and prognostication—this was real. As tangible proof, Barry has an Oscar on his mantle. I have this t-shirt.