Introduction: Great Expectations

A love letter to chaos, on both the big screen and the hardwood

I’ve been an NBA devotee just about as long as I can remember, but with the minor exception of a few-odd March Madness pools for chump change, I’ve never been a sports bettor. Even in those cases, with so little at stake, the stress it adds to the game is overwhelming. I can’t even imagine the anxiety of having a larger financial interest tied to perverse incentives like point spreads (I don’t need you to win, just not to lose by more than four and a half points) or the hyper-specificity of a parlay (I don’t just need you to win, you also need at least 26 rebounds and points combined, and if you lose the jump ball, this whole thing goes belly up before it starts), but in another sense I know exactly what it feels like.

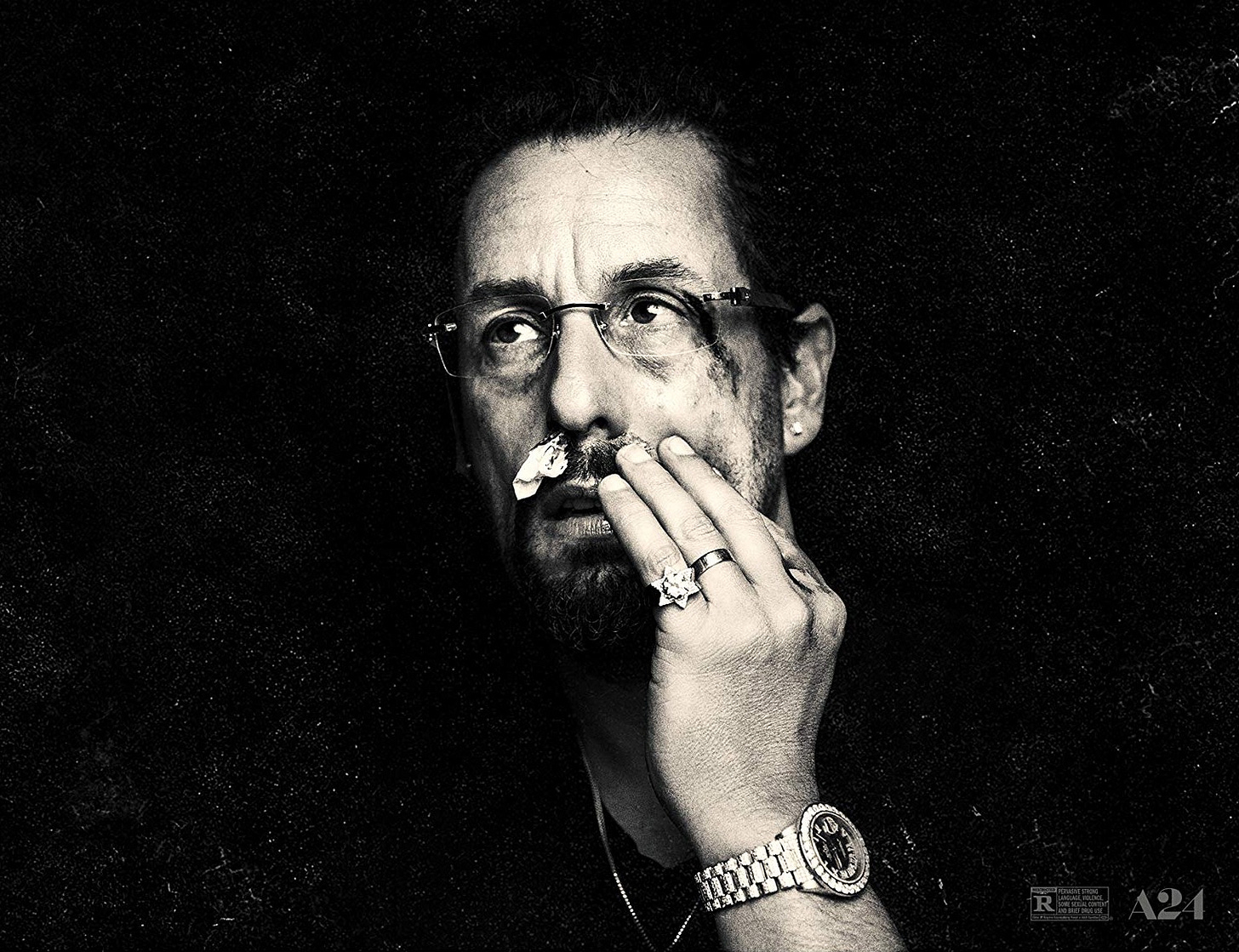

Sometime in 2018, details began to leak about the Safdie Brothers’ follow-up to 2017’s Good Time. Adam Sandler would star as a gambling addict in New York’s Diamond District, acting alongside basketball legend Kevin Garnett. The Weeknd was allegedly playing a 2012 version of himself. As teasers dropped, the iconography around the movie developed: a bloodied Sandler with tissue stuffed up his nose, a bejeweled Furby, the alluring black opal glow filling the trailer text. This was the directors cashing in their blank check for a high-leverage bet on a long-gestating passion project; if any one of these bizarre components misfired, the result could be a disaster.

As I sat in the theater on New Year’s Day 2020, I couldn’t help feeling a little anxious on their behalf, but that anxiety was quickly replaced by others. As Howard Ratner pings around the Diamond District, dodging creditors and pawning Peter to place a bet with Paul, we can already see the endgame: the house always wins. Sure enough, his reckless risk-taking takes him to some depressing places—locked naked in the trunk of his own car at his daughter’s middle school play, for one example—but the euphoria of finally nailing a massive $1.2 million gamble is priceless, even if it is short-lived. He explains as much to Garnett, speaking in language the notoriously intense (and notoriously foul-mouthed) competitor can understand, “I see you out there when the fucking stadium’s all booing you, you’re 30 up, you’re still going full tilt…c’mon KG, this is no different than that. This is me, all right? I’m not a fucking athlete. This is my fucking way. This is how I win.” For a moment, Howard—the ultimate underdog—had finally tasted victory.

Anything is possible, but betting odds indicate some things are more possible than others. In a way, Vegas is a publisher of public opinion, providing the best-calibrated consensus about who we think should win. What’s particularly fascinating to me is when that consensus is wrong, which is more frequent than you’d think. In an age of predictive model prosperity, with “advanced stats” having fully entered the NBA mainstream, there can be a creeping feeling that the game has been figured out, every play analyzed and optimized, and any mystery explainable with enough data. And yet, as datasets grow richer and models more sophisticated year-by-year, the preseason title favorites still lose more than half the time.

Uncut Gems provides this chaos a tangible form in the black opal, whose mysterious effect on Kevin Garnett drives the plot: a good game, bad game, good game sequence that mimics the volatility of Howard’s highly leveraged emotional state. Its mystery is never really explained, but I like to think of it as broadly representing the mystical, superstitious, emotional parts of the game—the “basketball gods”, the “hot hand”, and other alchemical elements that don’t make their way into Vegas’s calculations but make the improbable possible. I’ve always been drawn to the outliers; win or lose, it’s more fun to be surprised than to be right. Prognosticators peer into a crystal ball to see the future, but that’s a narrow purview. “They say you can see the whole universe in opals,” promises Howard. That’s infinitely more interesting.

I started this writing project after spending days of lockdown in 2020 watching (or re-watching) old NBA Finals games. It’s a different experience when you already know the outcome—like having a movie spoiled for you—but I found that digging up old betting odds provided invaluable context for what I was seeing.

Michael Jordan’s dominance in the nineties now feels like a foregone conclusion, but the likelihood of his Chicago Bulls winning all six titles they did was infinitesimal.

The San Antonio Spurs are treated as the platonic ideal of a basketball organization today, but throughout the aughts the Los Angeles Lakers’ star power blinded Vegas oddsmakers time and time again to Tim Duncan’s dull, subtle brilliance (to the peril of anyone betting against him).

Even as the superteam formations of the 2010s generated some of the most lopsided title odds in history, underdogs broke through at an alarming rate; when all was said and done, LeBron James’s promise of “Not one, not two, not three, …, not seven” titles in Miami only delivered two, and the Golden State Warriors’ dynasty came crashing down only three Earth-years after owner Joe Lacob boasted his franchise was “light-years ahead” of the pack.

Looking at all this history was like gazing into the black opal: a whole universe of complex, interlocking narratives worth telling. I’m not interested in sports betting or predicting the future. I’m here to write about the mesmerizing, chaotic past and present of a league that decides legacies by the fickle bouncing of a ball. This is me. This is how I win.